Last month’s newsletter was an overview of turning centers. This month we are going to look at ways to simplify your drawings with the express purpose of reducing the cost of manufacturing and inspection.

I am going to make an assumption for the sake of this newsletter that the machine shop making your parts is using 3D model-based programming and does not require a fully dimensioned drawing in order to do the programming. If that isn’t the case, please call me right now…we need to talk!

With 3D-based CAM programming, the need and intent of drawings has fundamentally changed. Back when drawings were created in only 2D, and the programmer may have re-drawn the part in their CAM package or programmed the part by hand; it was essential to have explicitly defined drawings with all features dimensioned. This is no longer the case but many companies still fully define the part on a 2D drawing. We aren’t sure why they do this. It is either that they haven’t thought about changing it – it’s the way they have always done it or it’s because they still have some suppliers who still need a fully dimensioned drawing because they haven’t graduated into 3D based programming. In either case, it is a wasteful practice (and by wasteful I mean in the Toyota Production System definition of waste as not value added) that is not necessary and not something your customer is willing to pay for. Does your company still fully define parts with 2D drawings? If so, maybe it is time to challenge this outmoded way of doing things.

In our opinion, drawings are no longer defining the geometry of a part. Because all of the tool paths are going to be defined by the 3D model in the CAM system many parts can be programmed and machined without any drawing at all. We often do this for prototyping work and even for some customers with production work. But there are invariably details that need to be communicated which cannot be gleaned from a generic model (e.g. IGES, STEP or other translated file). If you are using the same CAD/CAM system as your machine shop (such as Pro/E and Pro/MANUFACTURING) then the possibility to eliminate drawings entirely is very realistic. The details which most often need to be communicated on a drawing are typically these:

- Non-standard tolerances

- Threads

- Geometric tolerances

- Material

- Finishing requirements

- Hardware installation

For the items in the list above remember these important details:

- Use the number of significant digits appropriately on dimensions which you do put on the drawing. And make sure they match the tolerance block. It is also nice to always include the overall size in X,Y,Z – it makes estimating and planning faster and they can also often be reference dimensions which don’t need to be inspected.

- Make your dimension tolerances bilateral as described back in June 2009 (and ensure your 3D model is dead center at the nominal size). Unilateral tolerances are almost always harder to program and achieve good results.

- Don’t put a tight depth tolerances on your threads – it is rarely necessary as discussed in February 2009.

- Similarly, don’t specify tight tolerances on your chamfer diameters as discussed in July 2009.

- If you are going to specify a global note that undimensioned features are to be held to the 3D model, then use a note like we described back in May 2009. This is a big one as the inspection cost is SO much less. We still firmly believe that if you need to specify an exact tolerance because you don’t trust your machine shop you are working with the wrong supplier.

- If possible, specify the material on the face of your drawing. Having the material referred to on one or more layers deep of BOM (Bill of Materials) or external documents adds complexity and potential for error. Some companies specify material sizes as part of the material definition which can box a quality-conscious supplier into ineffective manufacturing practices. It is one thing if plate thickness is critical to strength requirements but leave the longitudinal and transverse dimensions unspecified (for more guidance on specifying material sizes please see December 2008). The same is true of hardware, finishing and plating requirements – list the exact specifications and/or part numbers on the print, rather than on an external BOM. It is also important not to specify this information in multiple places as conflicts are bound to result which will lead to wasted time if they are caught and resolved or non-conformances if they are not.

Some of the types of dimensions which are the most extraneous and which we recommend avoiding are:

- Locations for entire sets of holes, pockets or other repeating features. Maybe just specify one and leave the rest off, or leave them all off.

- Dimensions to virtual intersections.

- Dimensions to the tangent points of radii, and the center point of radii.

- Basically any other dimension which is controlled 100% by the G-Code of the CNC machine. These types of features are very unlikely to be wrong and only drive inspection cost. If you aren’t sure what will be controlled by the G-Code, then ask your machine shop.

As a final note, please make sure not to abuse your 3D CAD system’s dimension override feature when creating drawings. There is an incredible amount of waste generated by disagreements between drawings and models. No one stands to gain from having to remake parts. In the case of prototype parts, prototype machinists will program and machine the part to the model. Only after the part is machined is the feature verified against the drawing. If the model and subsequent program disagree with the drawing, the part will not meet the drawing. You can imagine the severity of this issue if we are only machining a single part. To prevent this issue, there would be an incredible amount of waste if the model and drawing had to be verified prior to programming and machining. It is better to eliminate this waste altogether at the drawing stage.

To summarize, focus on the features, tolerances, and attributes which are really important to you. These are the items which are critical that you communicate to the manufacturer so that they can focus on what you care about. If it isn’t as important to you then don’t over specify things. That way, everyone can work as lean as possible and focus on the value-added part of doing their jobs. A lean supply chain is an inexpensive supply chain.

Until next month. Thanks for reading.

Paul Van Metre

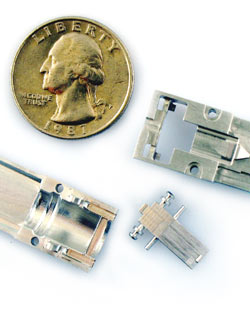

Every month we feature a really cool part that we have made. May’s Part of the Month is this set of small intricate machined parts. These required cutters as small as .016″ in diameter, included lots of surfacing, and some custom undercutting tools. It takes a lot of care to make tiny parts with high tolerances and cosmetics.