Last month’s newsletter discussed some of the factors related to tolerances that drive machined part cost. This month we are going to talk about threaded holes and threaded inserts. We will go into greater depth in future newsletters about other types of holes and threads.

Threaded holes can vary widely in cost. One thing to keep in mind is that depths of threaded holes are harder to control and costs can increase quickly for threaded holes with tight depth tolerances. The reasons behind the high costs are very low first part yield and requalifying a replacement tap and subsequent scrappage. The most common mistake is to leave a threaded hole depth dimension with 3 decimal places so it defaults to the title block tolerance (typically +/- .005″). The reason this is a problem is that taps are not very consistent between their tip and the first full thread. A “bottoming” tap typically has between 1.5 to 2.5 leading threads before the thread profile is complete. We can measure the tap and try to approximate the amount of lead for any specific tap but it is much easier to specify a looser depth tolerance. There aren’t many circumstances where the threaded hole needs to be held tightly. One circumstance this tolerance might need to be high is if you have a blind threaded hole where you need a minimum of threads but it can’t break out through the other side of your part. In these cases, we are generally faced with also having a very short distance between the bottom of the pre drilled hole and the bottom of the threads. Again here, the limiting factor on the distance between the full thread and the bottom of the hole is the tap itself.

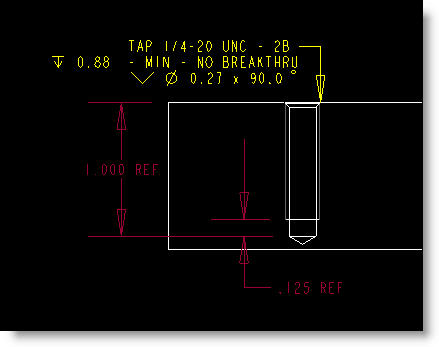

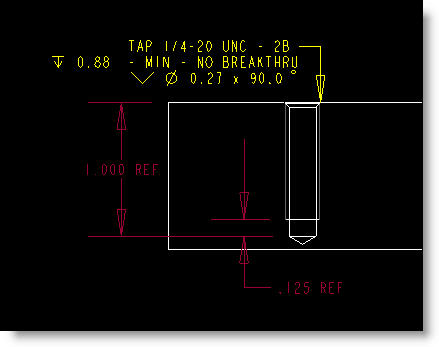

In figure A we see an example of a hole where the minimum distance from the shoulder of the drill to the first full thread is illustrated. In this case, a 1/4″-20 hole would need a minimum of .125″ (.05″ pitch x 2.5 threads). Any greater than that will not save money but any tighter than that will take more adjusting and cost more.

We also see in yellow text the most cost effective way to notate this thread on the drawing. The depth is called out as .88 min rather than .875. We also see that there is no pre-drill size specified. Cut and roll taps use different sized predrill holes so the predrill size should not be specified unless there is a very specific reason for doing so. The chamfer diameter in this example is also just two decimal places which is much less expensive than using three decimal places. To give an example of how costs can be affected by these tiny details, if this hole callout specified a predrill size, a .875 depth, a .270 chamfer and had less than .125″ clearance to the drill shoulder, this hole could easily cost 3x – 5X what it does as represented in yellow text.

Here are a few other notes about best practices or cost drivers for threaded holes. It is advisable to avoid 6-32 threads; the ratio of major to minor diameter is greater than other thread sizes which makes the tap more likely to break than other sizes. Also, don’t specify threaded holes that are deeper than you need. They become expensive as taps are more likely to break the deeper you go. If the thread depth is greater than your fastener will thread, the result is wasted money. If you do have a deep thread that is through the part, make sure you specify if all the threads need to be from one side or if tapping from both sides is acceptable. A shop might assume they can tap from both sides, in which case the threads will not be contiguous which may or may not work with your design.

Fig. A: How much clearance to leave and the cheapest way to specify the hole dimensions.

As mentioned above, threads such as in this example can be made with cutting taps, roll forming taps, or thread-milled. If executed well, formed threads are stronger than cut threads and the taps generally are stronger and last longer so they are less expensive to create. Formed threads have their own unique challenges for the shop though. If the minor diameter is not held extremely close then the threadform may not be perfect leading to issues with installing threaded inserts. Roll forming does not create chips down in the bottom of the hole which is an advantage. Some materials do not lend themselves to being formed though. Really hard and soft materials will generally be cut threaded and medium hardness materials like aluminum and softer steels respond well to roll forming. Generally though, leaving the option up to the manufacturer is advisable unless your situation specifically precludes an option.

Sometimes you need threads that are stronger or more durable than your base material can offer. In these cases a threaded insert is a good option. With plastics, the only realistic option is a heat staked or ultrasonic staked insert such as a PEM insert. They are inexpensive and easy to install. With metals, there are more choices. STI (Helicoil) inserts, Keenserts, and solid female threaded PEM inserts are all options. Generally speaking, Helicoils are less expensive to buy, install and service later. In our experience, engineers often specify threaded inserts but after discussing their needs threaded inserts are unnecessary. If you can engage your fastenener at least two times its diameter in threads, then even in aluminum there’s is a good chance the threads will be stronger than the fastener itself. Depending on the application, it may be cheaper in the long run to occasionally repair a thread than to specify them all as inserts. We estimate that a typical helicoil costs approximately an additional $1 – $3 to buy and install compared to a plain threaded hole. The bottom line is to really consider if you need that insert and try to transcend the argument that you need to include inserts because it ‘s the way your company has always done it.

Every month we feature a really cool part that we have made recently. February’s Part of the Month is a titanium deepsea housing cover. The housing face had to be carefully stitched. There wasn’t much room for error as the assembly is operated at depths of up to 9,840ft [3000m]. The result is a perfectly functional and attractive looking part.